4 Women scientists in the “they used my data” club

Celebrating 12 unacknowledged, unbelieved, and driven to obscurity Women Scientists over 3 articles leading up to the International Day of Women and Girls in Science on Feb 11th this year.

Women scientists face a rough deal.

Not surprising perhaps in earlier centuries, but I bet this is still going on and much more so than gets out in the public eye.

If only because nowadays doing it openly is politically incorrect. No one — including scientists, scientific institutions, and universities — wants a reputation for politically incorrectness. And scientists tend to be smart enough to come up with “plausible” reasons that at least sound politically correct.

Science regards any findings that go against “common” knowledge with skepticism, whether of female or male origin. But what happened to the 12 women in this article series goes way beyond that.

I’ve grouped them in three “societies”:

The “they used my data” club: 4 Women scientists who had their work appropriated and taken credit for by men.

The “ignored until I proved it twice” brigade: 3 Women scientists who faced incredulity about their findings, often having to prove it more than once, or have a man corroborate (repeat) their findings before being accepted.

The “low status, high impact” collective: 5 Women scientists who had to take positions at lower status institutes to be able to pursue their interests.

Note that many many women in the brigade and the collective are also members of the “they used my data” club.

This week’s society is the “they used my data” club. The other two follow in the next 2 weeks.

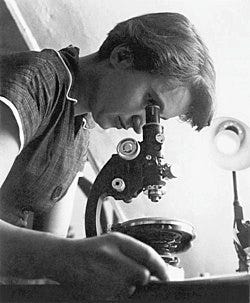

1. Rosalind Franklin, Molecular Biologist

In 1951, Rosalind Franklin produced Photo 51—the X-ray diffraction image that revealed DNA’s double helix structure. Her crystallography work was meticulous, her data irrefutable.

Without her knowledge or permission, Maurice Wilkins showed the image to James Watson. James Watson and Francis Crick used her findings to build their model, publishing in 1953 with no acknowledgment of Rosalind Franklin’s contribution.

When confronted, Rosalind Franklin didn’t fight for credit—she moved on to groundbreaking work on the tobacco mosaic virus and polio. She died of ovarian cancer in 1958, likely from years of radiation exposure in her research.

Four years later, James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins won the Nobel Prize.

Franklin’s legacy? The work speaks louder than the theft. Her techniques form the foundation of modern molecular biology.

2. Lise Meitner, Nuclear Physicist

In 1938, Lise Meitner was forced to flee Nazi Germany despite being one of Europe’s foremost nuclear scientists.

From Stockholm, she received a letter from her longtime collaborator Otto Hahn describing his latest uranium experiments.

She immediately understood what he didn’t: uranium was undergoing nuclear fission, splitting atoms and releasing tremendous energy.

She sent him the theoretical explanation. Hahn published without her—first author, no mention of Lise Meitner’s interpretation. In 1944, he alone won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Einstein called her “the German Marie Curie.” Niels Bohr stated she was “instrumental” in the discovery. But her name wasn’t on that initial paper, wasn’t on the Nobel citation, and gradually faded from the narrative.

She never stopped working. At 89, still conducting research, she declined attending the dedication ceremony for a German nuclear reactor—wanting no association with nuclear weapons.

3. Eunice Foote, Climate Scientist, Physicist

In 1856, Eunice Foote conducted a series of elegant experiments: glass cylinders filled with different gases, placed in sunlight, temperature measured.

Her results were clear—carbon dioxide trapped more heat than any other gas she tested. She theorized this had massive implications for Earth’s atmosphere and climate. She published her findings in the American Journal of Science.

But she wasn’t allowed to present at the scientific conference—a male colleague read her paper for her.

Three years later, Irish physicist John Tyndall published similar findings. He got credit for discovering the greenhouse effect.

For over 150 years, climate science textbooks cited John Tyndall, not Eunice Foote.

It wasn’t until 2011 that a researcher stumbled upon Eunice Foote’s original paper.

Now climate scientists are fighting to restore her name to the discovery that defines our era.

4. Chien-Shiung Wu, Experimental Physicist

In 1956, theoretical physicists Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang proposed that a fundamental law of physics—the conservation of parity1—might not hold in weak nuclear interactions.

Chien-Shiung Wu designed and executed the experiment to test it.

For months, she worked at near-absolute-zero temperatures with cobalt-60 atoms, building the apparatus, calibrating the instruments, running the trials. Her results were definitive: parity was violated.

The physics world was stunned.

In 1957, Lee and Yang won the Nobel Prize for the theory.

Chien-Shiung Wu, who did the experimental work that proved it, was excluded.

She never complained publicly, never demanded recognition. She kept working—on the Manhattan Project, on beta decay, on weak interactions.

Interesting trivium: “Wu was shocked at the sexism in American society when she learned that at Michigan women were not even allowed to use the front entrance, and decided that she would prefer to study at the more liberal Berkeley in California.”

Colleagues called her “the Chinese Madame Curie.” She called herself a scientist who happened to be doing the work.

Sources

Rosalind Franklin: National Geographic (2021), Smithsonian Magazine (2019)

Lise Meitner: National Geographic (2021), Oxford Royale (n.d.)

Eunice Foote: TED Ideas (2024), Oxford Royale (n.d.)

Chien-Shiung Wu: Physics.org (2022), BBC Science Focus (2025)

It’s to do with nature supposedly not distinguishing between left- and right-handedness (rotations). I’ve read the explanations. And while I’m in the top 2% of smartie pants, this particular subject is not in my wheelhouse — or the explanations are exemplary unclear. Obviously, I vote for the latter. Possibly they’re unclear because the author is afflicted with the curse of knowledge or doesn’t understand it well enough themself to be able explain it to a 5 year-old (yes, I’m 10+ times older than that, but … expressions).